It’s been two years since I received my PhD (and longer since I last updated my astronomy homepage). For posterity, I thought I’d add a short description of what I did back then to the new site.

For those who prefer video to reading, here’s a talk I gave way back in 2014 explaining in layperson’s terms the background of my research:

White Dwarfs

White dwarfs (WDs) are the incredibly dense, burnt-out husks of Sun-like stars after they extinguish their viable nuclear fuel, and are generally composed of carbon and oxygen (these are called CO white dwarfs, or CO WDs). Having no nuclear reactions of their own, WDs remain inert as they slowly shed what little heat they retained from their previous lives as stars.

It has been well-established, however, that a fraction of CO WDs are spared this ignominious fate, instead ending their lives in type Ia supernovae, the most energetic thermonuclear explosions in the universe. These supernovae are so bright they can be seen from billions of light years away, making them invaluable distance-markers in many fields of astronomy. A conundrum remains, though: why do otherwise inert stellar husks completely destroy themselves in thermonuclear explosions? The general consensus among researchers is that the WD is triggered by interacting with a companion star, which makes the interior of the WD either too dense or too hot, both of which can trigger explosive nuclear fusion. The exact nature of that trigger remains highly disputed to this day and a diversity of scenarios have been proposed and require further investigation.

White Dwarf Mergers

My thesis utilizes computer hydrodynamics simulations to examine the merger of two CO WDs - when two WDs orbiting one another get close enough to tear each other apart through tidal effects.

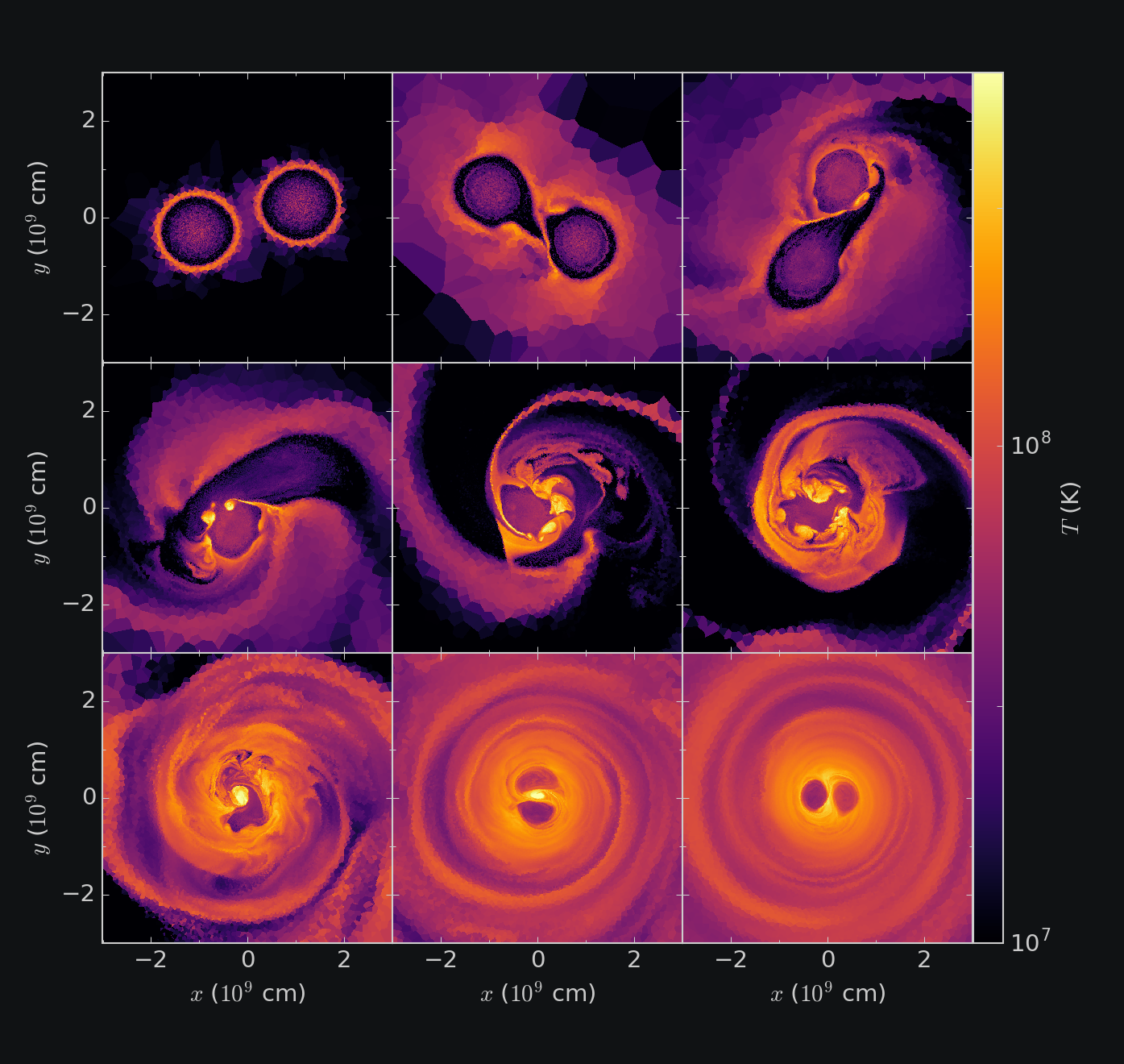

Here’s a series of snapshots representing the temperature evolution of a pair of merging WDs within one of my simulations.

In nature, binary white dwarfs evolve from binary star systems, and the two white dwarfs are drawn closer together though a general relativistic effect that saps their angular momentum. The simulation starts just at the start of the merger. The white dwarfs respond to each other’s gravitational pull, and deform into teardrop shapes. For material at the tips of each teardrop, the gravitational pull of the companion WD is actually stronger than that of its own. This is what causes material to transfer between the WDs - the imbalance of transfer is due to the two WDs having slightly different masses. At locations where material from WD impacts the other, temperatures are raised to more than half a billion degrees (the yellow regins in the panels above). The rate of transfer increases with time, and eventually becomes so extreme that the less massive WD is torn apart, merging with the more massive one into a single object.

I specifically looked into a scenario proposed by my supervisor in 2010 that hinges on the merged object, or “merger remnant”, becoming hot enough to trigger explosive nuclear fusion. While only mergers between the most massive (and by far most rare) CO WDs could become hot enough to explode during or immediately after the merger, mergers between CO WDs whose masses differ by less than a tenth of a solar mass lead to hot, rapidly rotating merger remnants. These could subsequently explode.

Evolution of the Merger Remnant

Following the merger, the remnant is spinning rapidly, but will quickly slow down from the influence of magnetic fields. This slowdown leads to heating, and for mergers between similar mass CO WDs, the heating could be enough to trigger carbon fusion.

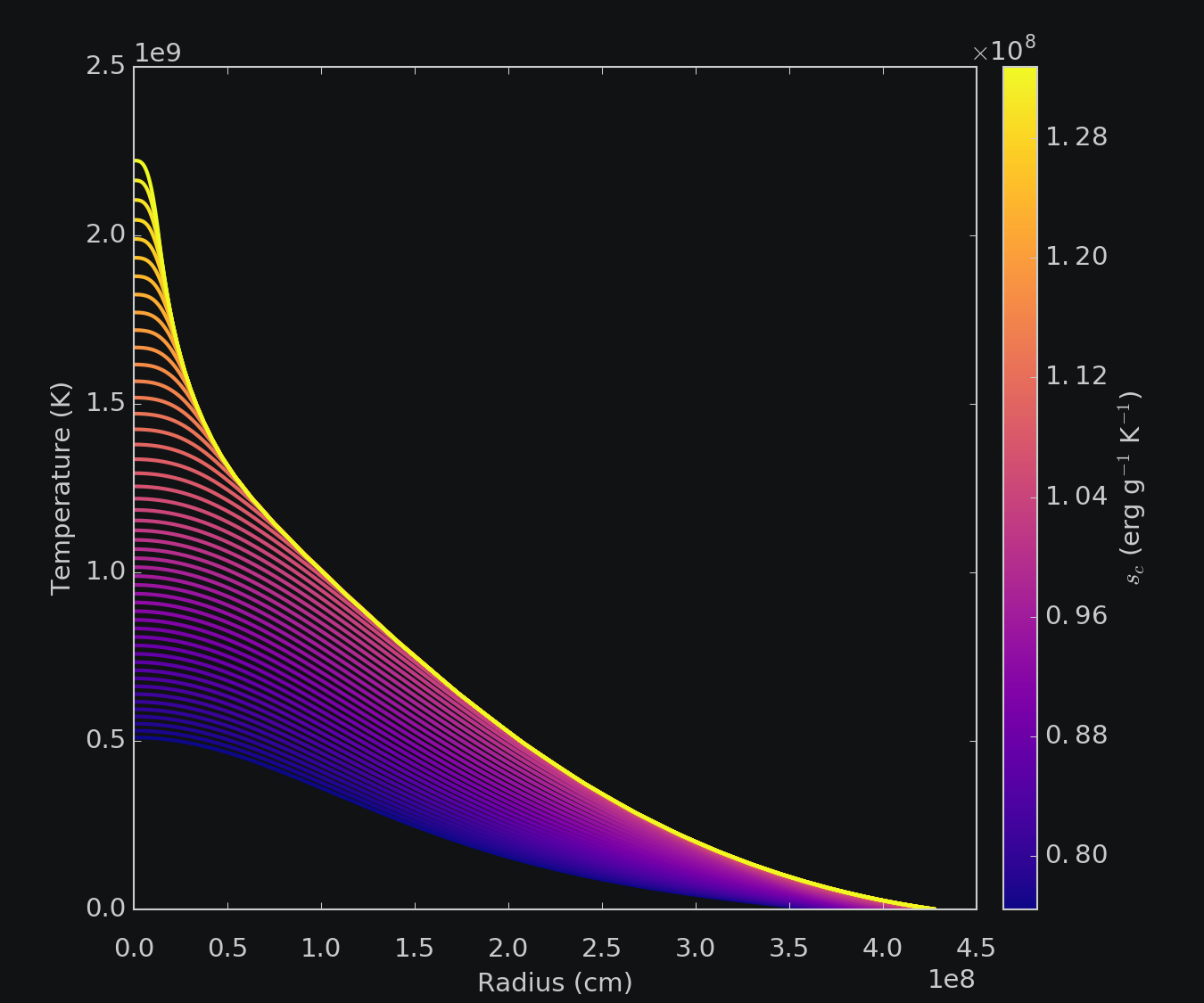

To investigate what happens after fusion is ignited, I created simulations of merger remnants experiencing fusion in their center. The evolution of one such remnant is charted below:

The heat generated by the fusion raises the temperature of the CO WD, which in turn hastens the rate of fusion. For the most massive, and rare, merger remnants, this hastening could eventually lead to an explosion. Less massive ones, however, begin to expand before exploding, and this expansion effectively stabilizes the fusion rate.

Various theoretical calculations and observations of the CO WD population indicate that, if only the most massive mergers lead to explosions, they would be far too rare to explain the majority of type Ia supernovae.

Future Prospects

So, where does that leave us? One complication is the creation of powerful magnetic fields by the merging process, which I showed with one of my simulations. While we know these fields will slow down the merger remnant’s spin, they have not been properly included in studies of post-merger evolution and of CO WDs undergoing fusion. A preliminary estimate in my thesis hints that magnetic fields could dramatically lower the mass required for fusion to hasten and produce an explosion.

Other groups have found success with a scenario that uses a small amount of helium (naturally occuring on CO WDs) as a “lighter fluid” - helium explodes at a lower temperature than carbon, and a helium explosion could trigger a carbon one.

More information about all of this can, of course, be found under my thesis. It’s available on the TSpace thesis repository, or on the Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics library site (pdf link).

Share this page:

Twitter Facebook LinkedIn